'The Congressional Friends of Ireland and the Anglo-Irish Agreement, 1981-1985, by Andrew J. Wilson[Key_Events] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] AIA: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Document] [Description] [Reaction] [Assessment] [Aftermath] [Sources] The following chapter has been contributed by the author Andrew J. Wilson, with the permission of The Blackstaff Press Limited. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions. This chapter is taken from the book:

Orders to local bookshops or:

This chapter is copyright Andrew J. Wilson 1995 and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publisher. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, The Blackstaff Press Limited. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

AND THE ANGLO-IRISH AGREEMENT, 1981-1985 The rejuvenation of Irish-American republicanism in the early 1980s greatly alarmed both the US government and constitutional nationalists. Yet despite the series of legal and publicity defeats, the forces working against the IRA network did achieve their own successes. American law-enforcement agencies persistently hounded Noraid and secured convictions in a number of important gunrunning conspiracies. The Friends of Ireland continued to play an influential role in Ulster politics and made a significant contribution to the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985. From 1981, the Reagan administration intensified the FARA court case against Noraid. Federal attorneys worked relentlessly to force the group to acknowledge the Provisional IRA as its foreign principal. This legal action also had the objective of making Noraid provide greater details about its fund-raising activities. The Justice Department hoped that victory in the case would bolster its contention that Noraid was bankrolling IRA violence in Northern Ireland. Noraid fought a prolonged legal battle against the Justice Department but in May 1981, Judge Charles Haight, Jr., finally ruled that the group must register as an agent of the Provos. A Federal Court of Appeals upheld the Haight verdict in January 1982. Noraid continued the legal controversy by refusing to file its returns under the FARA. In early 1984, the Justice Department successfully charged the group with contempt of court. It was given ninety days to comply with the Haight ruling or risk a hefty fine. In this situation, Noraid agreed to register the IRA as its foreign principal but insisted on including a written disclaimer against the court ruling. Federal attorneys agreed to this, and Noraid resumed filing its financial returns in July 1984. With enforcement of the Haight ruling, the Justice Department could show that Noraid was officially registered as an agent of the IRA. This bolstered US government claims that the group supported violence. As noted earlier, however, there is little evidence to show that this formal legal connection had any detrimental effects on membership or financial support. In conjunction with the FARA case, the State Department also tried to weaken the republican network by tightening its visa denial policy. The most noted example was the continued refusal to permit Gerry Adams entry to the United States, despite his election to the British Parliament in 1983. Adams received numerous invitations to speak in America but each visa application was refused on the basis of his support of violence. His case became a cause célèbre for Irish-American republicans. A Committee for Free Speech in Northern Ireland formed specifically to win a visa for Adams, while members of the Ad Hoc Committee repeatedly appealed to the State Department to lift their ban. Prominent republicans admitted that the visa denial policy seriously impeded their activities and effectively undermined the presentation of Sinn Fein's position in America.[1] Yet militant nationalists did reap some benefits from the fact that many leading newspapers, especially The New York Times, strongly attacked the visa denials for "damaging America's reputation as an open society of intelligent, free citizens, capable of deciding for themselves whether to hear or ignore a speaker."[2] A number of republicans were able to enter the US illegally. Canadian sympathizers organized an "underground railway" through which members of Sinn Fein and the IRA would be provided with forged documents and escorted across the American border. Some participated in clandestine fund raising and weapons procurement ventures while others simply tried to blend into society and avoid federal agents. In the early 1980s, US immigration officers began investigating this Canadian pipeline and conducted surveillance of republican suspects under "Operation Shamrock." Information from this investigation led to the apprehension of Owen Carron and Danny Morrison in January 1982. Shortly afterward, agents captured Edward Howell and Desmond Ellis as they were trying to enter the United States illegally at the Whirlpool Bridge near Niagara Falls. The authorities described both men as key IRA explosives experts.[3] Fear of arrest temporarily blocked the Canadian route for illegal entry but did not stop republicans from getting to America. Joe Cahill and Jimmy Drumm, for example, were caught in New York City in May 1984 after using false immigration documents. The two men were suspected of organizing an arms shipment for the IRA. Although they were not formally charged with this conspiracy, they were deported to Ireland.[4]

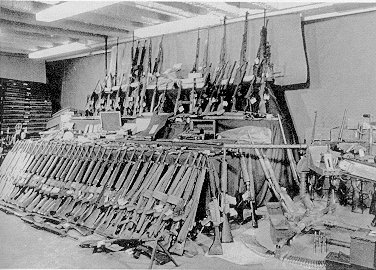

The most effective measures taken by US law enforcement agencies, however, were against IRA gunrunning. Despite the failure of and embarrassment from the Harrison/Flannery case, FBI agents continued their undercover operations. One of the first successful convictions in the period was the case of Barney McKeon. In 1979 George Harrison acquired a large consignment of arms stolen from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Before shipment to Ireland, the weapons were stored in a garage belonging to Barney McKeon, an American citizen originally from Northern Ireland who was very active in Noraid. Before the arms shipment left New York, one of the conspirators telephoned IRA contacts in Dublin and gave details of its arrival. Irish detectives recorded the call from a wire tap and immediately informed their counterparts in America of the gunrunning scheme.[5] When the weapons arrived in Dublin in late October 1979, Irish authorities laid a trap for the IRA. The Provos learned of it, and no one appeared to collect them. The Gardai were forced to seize the arms on November 2, 1979. Some of the rifles had intact serial numbers and could be traced to George De Meo. Police also found a shipping document that linked the weapons to Barney McKeon. From this mistake, McKeon was convicted on June 24, 1983, of conspiracy to export weapons to the IRA. He received three years' imprisonment and a fine of $10,000. Although McKeown was jailed and the arms-supply line broken, the court case produced a major controversy which greatly embarrassed American law enforcement agencies. During the first trial, in December 1982 (which ended in a hung jury), Stephen Rogers, a senior US Customs official who had supervised gunrunning investigations in New York, testified on behalf of McKeon. Rogers said he did this because of "serious wrong-doing" by the prosecution. He alleged that Joseph King, a US Customs agent, had perjured himself by telling the court he did not know of the Garda telephone tap in Dublin. Rogers claimed that King knew of the covert surveillance from its inception.[6] After McKeon's conviction, the controversy over Rogers's testimony continued. British and Irish officials were infuriated by his revelations. They were particularly incensed because Rogers disclosed details of a secret meeting between British intelligence and US law-enforcement agents. Further, he named British intelligence officers in open court. Reports circulated that both the British and Irish authorities began withholding information because of their lack of confidence in the US Customs Service. In response an internal investigation of New York customs agents was launched to uncover alleged IRA sympathizers. Later William von Raab, the commissioner for customs, traveled to London and Dublin to reassure both governments that there were no republican informers within his service.[7] On November 1984, Stephen Rogers was fired from the Customs Service because of his conduct at the McKeown trial. He brought unfair dismissal proceedings before the Federal Merit Systems Protection Board in May 1985. Rogers demanded that secret documents outlining the role of British and Irish agents in the McKeon case be made available for his defense. Reports allege that British intelligence made it clear to the US authorities it did not want any more confidential information disclosed to the public. Without this information, which Rogers claimed was essential, the Board reinstated him with back pay. It also concluded that Rogers's naming of the British agent was "inadvertent rather than a result of IRA sympathy."[8] Government agents were investigating other gunrunning operations, one of which was an arms conspiracy led by Gabriel Megahey and involving perhaps eleven other republican sympathizers. Megahey was born in Belfast and had a long connection with the republican movement. He worked in England for many years at the Southampton docks. In the mid-seventies he was expelled from the country because of his involvement in a scheme to import explosives and weapons from New York. Megahey then went to America and worked as a bartender in Queens. He maintained his republican connections and was alleged to be leader of the IRA in the United States. Megahey was also involved in gunrunning and soon became the focus of FBI surveillance.[9] When Desmond Ellis and Edward Howell were arrested crossing the Canadian border in February 1982, Gabriel Megahey's name was found on their shopping list for weapons. The FBI put a tap on Megahey's phone. They recorded his alarm at the arrest of the two men but were unable to get hard evidence linking him to IRA gunrunning. The FBI investigation of Megahey took an unexpected turn when Michael Hanratty approached government agents and offered to help smash the arms conspiracy. Hanratty, an electronics surveillance expert, was contacted by Andrew Duggan in June 1981 for help in purchasing sophisticated technical devices for remote-control bombs. Duggan, an Irish American active in Noraid, was a main figure in the Megahey network. He told Hanratty they wanted to send a large consignment of military material to the IRA. Hanratty claimed he turned informer for "patriotic reasons." He began cooperating in an FBI sting operation. He and agent Enrique Ghimenti, who posed as an arms dealer, arranged a meeting with Duggan in New York. The FBI had the room bugged and also installed a video camera. The operation was only partly successful because Duggan sat down in the wrong place and only his voice was recorded. Duggan was interested in the arms sale Ghimenti proposed. At a second meeting, this time in New Orleans, agents filmed Duggan and two IRA fugitives agreeing to buy five Redeye missiles at $10,000 each. The IRA men also asked for a whole range of automatic rifles, machine guns, and even a mini-submarine. At a third meeting, Megahey appeared and was filmed affirming the order for Redeyes. He also proposed that a hostage from each side should be held until the arms deal was complete.[10] The FBI operation reached a climax in June t982 when Megahey and his co-conspirators tried to send a consignment of fifty-one rifles and remote-control devices to Ireland. The weapons were packed into a container labeled "roller skates and comforters." United States agents working in close cooperation with their British and Irish counterparts seized the arms at Port Newark but allowed a small consignment to travel on to Limerick on board a cargo ship. When the weapons arrived in Ireland, Gairdai apprehended two IRA men sent to pickup the container. The men, Patrick McVeigh and John Moloney, were later jailed for seven and three years respectively for possession of an Armalite rifle and IRA membership.[11] On June 21, 1982, the FBI arrested Megahey and Duggan at a construction site in Manhattan. They also apprehended two brothers from Northern Ireland, Colm and Eamonn Meehan, who were involved in the conspiracy. The four immediately received legal aid from Irish-American republicans, and a panel of lawyers began investigating ways to thwart the prosecution.[12] Attorneys for the Meehans based their defense on the fact the brothers had been held as internees in Long Kesh. They claimed that the two suffered from post-trauma distress disorder, because of their experience in prison, and entered a plea of not guilty because of insanity. The Meehans were examined by a psychiatrist who concluded their claim to insanity was "only a diagnostic possibility." Judge Charles Sifton denied their defense. When this line of defense collapsed, lawyers for the four men copied the tactic used in the Flannery trial. They claimed the defendants thought Michael Hanratty was a CIA agent and therefore that their gunrunning scheme had US government approval. Assistant US Attorney Carol Amon produced CIA affidavits stating that Hanratty was not one of their operatives. Defense lawyers focussed on the involvement of British intelligence in the case and unsuccessfully tried to force FBI witnesses to divulge classified information. The trial lasted for nine weeks. On May 13, 1983, after five days of deliberation, the jury found the men guilty on most charges. As Gabriel Megahey was the leader of the arms conspiracy, he received seven years' imprisonment.'[13] Andrew Duggan and Eamonn Meehan each got three. Colm Meehan received two, following his acquittal on some of the conspiracy charges.[14] Following this victory, federal agents continued to investigate others who were suspected of involvement in the Megahey conspiracy. Their attempts to secure further convictions had mixed results. Patrick McParland, an associate of Megahey, fled to Ireland when he heard of the FBI sting. After months on the run he decided to surrender and voluntarily return for trial. McParland's lawyers successfully argued that although he had transported boxes of weapons for the Meehan brothers, he did not know their contents. In November 1983, he was acquitted on all charges.[15] In April 1985, the FBI arrested Liam Ryan and charged him with using false documents to purchase three Armalite rifles that were part of the Megahey consignment. Ryan, a naturalized American citizen, originally from County Tyrone, was alleged to be the IRA's officer-in-command in New York. He had close associations with Irish-American republican groups and was a personal friend of Martin Galvin. Agents matched Ryan's fingerprints with those found on the armalites and on the falsified purchase certificates. In September 1985 he pleaded guilty to making fraudulent statements in buying the weapons and received a suspended sentence.[16] The largest and most intriguing gunrunning operation to be uncovered in this period involved John Crawley. Born in New York in 1957, Crawley moved to Dublin with his family as a teenager. In 1975 he returned to the United States to join the military. After four years' service, Crawley went back to Dublin and became involved with the IRA. In 1984 he was sent to Boston to help assemble a $1.2 million arms cache for the Provos, which included machine guns, missile warheads, grenades, night sights, and flack jackets. In mid-September 1984, Crawley loaded the arsenal on board a fishing vessel called the Valhalla and sailed out of Boston bound for Ireland. Unknown to him and his associates, an informer had alerted the authorities about the conspiracy. This initiated a joint surveillance operation involving American, British, and Irish authorities. Reports surfaced that as the Valhalla sailed across the Atlantic, it was tracked by an American satellite which closely monitored the ship's progress. A crack force of Garda detectives joined to monitor the Irish end of the operation. Two Irish navy corvettes, the Emer and Aisling, followed a rendezvous ship, the Marita Ann, as it left port in Kerry. While the arms were transferred between the two trawlers in mid-Atlantic, a Royal Navy Nimrod aircraft photographed the operation with special magnifying cameras.[17]

Irish authorities intercepted the Marita Ann as it sailed

back to its home port laden with weapons. On board, they found

five crew members including Crawley and Martin Ferris, a prominent

Kerry republican and suspected member of the IRA Army Council.

The men were tried and convicted in the Special Criminal Court

on December 11, 1984. Crawley, Ferris, and Nick Browne, the ship's

captain, were each given ten years' imprisonment. Two crew members

who claimed they did not know about the Marita Ann 's mission,

received five-year suspended sentences.

on display at Garda headquarters in Dublin. UPI/BETTMANN Despite international security cooperation, the Valhalla slipped past US authorities on its homeward voyage with two IRA fugitives on board. The trawler was in port for three days before its discovery by customs officers on October i6, 1984. Federal agents began an investigation that eventually linked the gunrunning operation to organized crime in Boston and to drug trafficking. It was not until April 1986, however, that a grand jury indicted a group of men accused of involvement in the conspiracy. The leading figure in the indictment was Joseph Murray, an Irish-American from Charlestown, Massachusetts. Murray was a principal figure in the Boston underworld and had connections with the IRA and drug trafficking. When police raided Murray's home they found a consignment of weapons and over more than ten thousand rounds of ammunition. He was charged with conspiracy to supply guns to the IRA and with smuggling thirty-six tons of marijuana into Boston to pay for them.[18] Among others indicted were Patrick Nee, who was accused of playing a major role in acquiring the weapons. Nee was born in Ireland and, like Murray, was involved in Boston's organized crime network.[19] Robert Anderson, captain of the Valhalla, was also charged with gunrunning and was allegedly paid $10,000 by Murray for undertaking the voyage. Anderson was noted for his swashbuckling lifestyle and had used the Valhalla for a number of drug-running ventures. As part of a bargain with the government, in May 1987 the three men pleaded guilty to gunrunning. Prosecutors dropped the drug charges and recommended sentences for less than the twenty-two-year maximum. Murray was sentenced to ten years, while Patrick Nee and Robert Anderson got four years each. The trial was a major news item on both sides of the Atlantic because of its exposure of links between IRA gunrunning and organized crime in Boston. It also uncovered connections between Murray and Dr. William Herbert, an ambassador to the United Nations for the Caribbean islands of St. Kitts and Nevis. The trial revealed that Murray used Herbert to launder money he made from drug deals. The ambassador resigned in April 1987 when the FBI produced documents showing his connections with Murray.[20] A controversy also developed over the case of John Mcintyre, one of the crewmen on the Valhalla. He was questioned by customs agents after the ship's seizure in Boston. McIntyre had been cooperating in a federal sting operation against Joe Murray, but he disappeared soon afterward and has never been found. John Loftus, the McIntyre family lawyer, later co-authored a book entitled, Valhalla's Wake. He claims that John McIntyre was murdered in the US by two British agents in order to protect the IRA mole who had supplied information on the Marita Ann operation. In The iRA: A History, Tim Pat Coogan maintains that this smoke screen did not fool the Provos, and they subsequently executed the informer in Ireland. British and American authorities deny all these allegations but many unresolved issues remain in the case.[21] A final controversy emerged over the involvement of police officers in the Marita Ann affair. When the ship was seized, Irish detectives discovered eleven bullet-proof vests. Ten of these were subsequently traced to Charles Tourkantonis and Michael Hanley, both officers with the Boston Police Department. An internal investigation revealed that the two officers had bought the vests for John Crawley. No disciplinary proceedings were taken, however, because the officers claimed they did not know the flack jackets were to be used illegally.[22] The convictions secured by US law enforcement agencies against the gunrunning network in the mid-198os caused serious problems for the IRA. After the seizure of the Marita Ann, the Provos began to concentrate their arms procurement ventures in Europe and the Middle East. Although the IRA continued to ship some weapons from America, US authorities successfully undermined the transatlantic arms network.[23] In addition to these problems, Irish-American republicanism continued to suffer from the adverse publicity generated by IRA bombings. Attacks such as the Hyde Park bombs of 1982 and the explosion at the 1984 Conservative Party Conference in Brighton were given prominent coverage in the United States. Each initiated further criticism of the IRA. The strongest reaction against the Provos came after the bombing of Harrods department store in London on December 19, 1983. An IRA unit drove two cars packed with explosives and parked them outside the building. They phoned a warning that was hopelessly late for police to clear the streets. The bombs ripped through Christmas shoppers, killing eight and severely injuring many others. Kenneth Salvesen, a businessman from Chicago, was among the dead and three other Americans were injured. The bombing caused outraged reactions in Britain and Ireland, while the death of Salvesen brought some of the strongest attacks on Noraid ever launched in the American press. Numerous editorials alleged Noraid money had directly financed the bombs, and, therefore, brought death and injury to US citizens. Martin Galvin, recognizing the disastrous effect of the bomb in America, claimed that the action was taken without the Army Council's authority and that a warning beforehand "showed a principled morality that divides the freedom fighter from the terrorist."[24] Galvin's defense of the IRA led only to greater condemnations of Noraid in the American press. The inaccuracy of his statement was exposed later when evidence showed that the IRA team was on an official mission that had indeed been approved by the Army Council.25 The American ambassador in London attacked the IRA's "savage bestiality"; the Friends of Ireland called the attack "despicable and deranged." The Chicago Tribune's reaction to the Hyde Park attack was representative of most American editorial opinion on IRA bombings: IRA front groups. . . claim that they are raising funds for the families of slain or imprisoned IRA men. They lie. The money goes for arms, ammunition, and bombs. It buys the high explosives and the remote control detonators that blew up in London. The money bank rolls the sort of sub-humans who can pack six inch nails around a bomb and put it in a place where women and children and tourists will gather.[26]

The Friends of Ireland used every IRA atrocity to convince Irish Americans of the futility of violence. In addition, they continued to exert their influence on Capitol Hill to encourage new political initiatives in Ulster. Eventually, through close cooperation with the SDLP and Irish government, the Friends played an important role in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985. Pressure and influence from these Irish-American political leaders was, at certain stages, an integral factor in bringing the Agreement to fruition. The Anglo-Irish Agreement was very much a consequence of the political changes in Ulster after the hunger strike. Sinn Fein electoral victories, during and after the prison dispute, created intense pressure on the SDLP. John Hume realized that his party needed a major political achievement if it was to resist the challenge from republicanism. He hoped to secure concessions from the British government through direct Anglo-Irish negotiations. Yet the likelihood of securing this objective seemed remote. In 1982 the British were intent on pursuing an internal solution by devolved government through the establishment of James Prior's Assembly. They were consequently unresponsive to the Anglo-Irish dimension. Hume's hope of achieving a political breakthrough was further eroded by the chill in Anglo-Irish relations that began after Charles Haughey's electoral victory in March 1982. The new Taoiseach antagonized Margaret Thatcher with his nationalistic rhetoric and strong attacks against the Prior Assembly. Anglo-Irish relations reached their lowest ebb during the Falklands War. Haughey gave the Thatcher government only limited and grudging support to economic sanctions enforced by the EEC on Argentina and made a forceful condemnation of the sinking of the battleship Belgrano. In Maggie: An Intimate Portrait of a Woman in Power, Chris Ogden claims that the British prime minister considered Irish actions as an "unforgivable betrayal." He says it reinforced her "natural antipathy toward the Irish, whom she considered, in large part, shiftless, sniveling, and spineless."[27] These Anglo-Irish antagonisms greatly concerned the Friends of Ireland. The group was alarmed at positive republican publicity over the Flannery trial and the St. Patrick's Day Parade controversy. Senator Edward Kennedy and Tip O'Neill were frustrated that they could not counteract Irish-American republicanism by pointing to some political advances by constitutional nationalists in Ireland. Their frustration was compounded by the deterioration in relations between London and Dublin which seemed to block fresh political initiatives in Ulster.[28] In this unpromising situation, the Friends of Ireland worked for a political breakthrough. In their 1982 St. Patrick's Day statement they appealed for greater dialogue between the Haughey and Thatcher administrations. In May the Friends sent a delegation to Ireland led by Congressman Tom Foley and Senator Chris Dodd. They helped form a counterpart to the Friends of Ireland in the Dail called the Irish-US Parliamentary Group. This new organization aimed at strengthening transatlantic communications between constitutional nationalists in order to coordinate political action on Capitol Hill. The Friends of Ireland delegation also traveled to Belfast and met Lord Gowrie of the Northern Ireland Office. Congressman Foley and Senator Dodd told him they were concerned about the lack of political progress in Ulster and endorsed the Anglo-Irish approach as the best way forward. In order to show the British their commitment, key members of the Friends tabled joint-congressional resolutions calling for a ban on the use of plastic bullets and the outlawing of the Ulster Defense Association. Sinn Fein's success in the October 1982 Assembly elections was a major blow to constitutional nationalism. The results confirmed John Hume's view that a new initiative was imperative to consolidate the SDLP's position and counteract the rising republican threat. He began to press Garret FitzGerald, elected Taoiseach in December 1982, to embark on a new political drive aimed at defining the objectives of constitutional nationalists. FitzGerald was intensely aware of the threat posed by Sinn Fein and announced the formation of a New Ireland Forum. The New Ireland Forum began discussions in late May 1983. All constitutional nationalist parties submitted proposals on how to unify Ireland while still protecting the Protestant/unionist identity. Sinn Fein was not asked to participate, because of its support of violence; all Unionist political parties rejected the exercise as "obviously biased" against their interests. Despite frequent disagreements between the parties involved, the Forum continued to take testimony and discuss political alternatives throughout the year. John Hume and the FitzGerald administration were committed to getting support for the Forum from the Friends of Ireland. Before the discussions began, Hume contacted all his associates in Washington and asked for a firm endorsement of the new initiative. Together they formulated a "United Ireland" resolution, which was sponsored by twenty-eight senators and fifty-three congressmen. The resolution was issued on St. Patrick's Day 1983 and gave strong support to the New Ireland Forum, describing it as a great sign of hope for the peaceful unification of Ireland. The Friends repeated their attack on James Prior's "unworkable" Assembly and maintained that a real solution would require, "the bold cooperation of both the British and Irish governments jointly pursuing, at the highest levels, a new strategy of reconciliation."[29] The Irish Times described the resolution as "the most important Irish initiative to be put to Congress since 1920."[30] John Hume and Irish Foreign Minister Peter Barry traveled to Washington to support the resolution. Barry also held extensive discussions with Ronald Reagan and asked for support for the New Ireland Forum. The president was impressed by the new initiative. Although he maintained the traditional position that the United States would not chart a course for Ulster, he acknowledged that "we do have an obligation to urge our long-time friends in that part of the world to seek reconciliation."[31] As the New Ireland Forum discussions progressed, the Friends of Ireland were kept informed of the latest developments. On July 27, 1983, a delegation from Dail Eireann traveled to Washington and met with their American counterparts. Members of the Friends considered the visit so important they suspended confirmation hearings for Paul Volcker as Federal Reserve chairman in order to meet the Irish politicians. The discussions concentrated on a growing conflict within the Forum between Charles Haughey and Garret FitzGerald. Press reports in Ireland and America suggested Haughey was using the Forum as a means to embarass the Taoiseach. This political maneuvering alarmed the Friends. Journalist Michael Kilian of the Chicago Tribune, contends that they asked the Dail delegation to advise Haughey not to disrupt the discussions. Tip O'Neill stressed that the Forum needed to present a united front in order to win the support of the United States government and to enhance constitutional nationalist efforts on Capitol Hill.[32] The Friends of Ireland tried to aid the Forum by continuing to encourage meaningful dialogue between the Irish and British governments. In October 1983 they sponsored a resolution calling on President Reagan to appoint a special US envoy to Northern Ireland. In an accompanying statement, Senator Edward Kennedy said an American envoy could play an important role in encouraging Anglo-Irish talks. Although the proposal was rejected by the Reagan administration, it did give the British yet another indication of the Irish-American concern to see a new political move in Ulster.[33] The Forum Report was finally released in May 1984 and offered three political options as possible solutions to the Ulster conflict. After strong pressure from Charles Haughey, it proposed that "the most favored solution" was a united Ireland, safeguarding unionist rights. The report also suggested a highly complicated federal-confederal system. Under this formula, both parts of Ireland would have their own assembly, presided over by a national government. The final option proposed that Northern Ireland could be ruled jointly by both the Dublin and Westminster governments. The Friends of Ireland immediately supported the Forum Report and began working for the endorsement of the Reagan administration. To enhance this effort, Peter Barry flew to Washington on May 4, 1984, and held high-level discussions with State Department officials. The talks proved successful and the US government later praised "the Irish statesmen for their courageous and forthright efforts embodied in the New Ireland Forum."[34] The British Parliament debated the Forum Report on July 2, 1984. There was considerable praise for its attempt to accommodate unionist aspirations and its strong condemnation of terrorism. The Thatcher government refused to give an official reaction until the next scheduled Anglo-Irish summit in November. There was widespread anticipation on both sides of the Atlantic that the British prime minister would make a magnanimous gesture toward constitutional nationalism. The Anglo-Irish summit was held at Thatcher's retreat, Chequers, on November 15, 1984. Since the release of the Forum Report, both governments had been conducting private discussions which would lay the basis for the Anglo-Irish Agreement. At Chequers, Garret FitzGerald tried to move these talks to a higher level. He suggested a political formula under which his government would amend articles two and three of the Irish constitution, which claim sovereignty over Northern Ireland. The Taoiseach hoped that in exchange, Britain would agree to a formal political role for Dublin in Ulster's affairs. Secretary of State Douglas Hurd opposed FitzGerald's offer. He felt the constitutional amendment was too great a gamble and would be extremely counterproductive if it failed. Consequently, the British delegation tried to retard the pace of discussions. Although both governments continued to work toward an Anglo-Irish agreement, FitzGerald recalled, "The British were tending to pull back from what had been discussed already. It was a somewhat disappointing meeting because the negotiations were moved to a lower and subtractive level."[35]Following the meeting at Chequers, Margaret Thatcher held a press conference. For the first forty-five minutes she gave a very positive appraisal of Anglo-Irish negotiations. When she was asked about the three political options advanced in the Forum Report, however, she dismissed them all in her now-infamous "Out, Out, Out" remarks. Thatcher's s seemingly insensitive reaction to the efforts of constitutional nationalists caused an immediate political backlash in Ireland. The normally restrained Irish Times said the prime minister was "as offhand and patronizing as she is callous and imperious." The Irish Press said Thatcher's vehement delivery had an element of rudeness usually reserved for bitter enemies and that she made "Out" sound like a four-letter word. The newspaper concluded her statement was a devastating rejection of all the hopes and efforts that went into the Forum. Relations between the London and Dublin governments entered a period of confusion and misunderstanding after Thatcher's press conference. Many Irish politicians believed the British prime minister was deliberately trying to humiliate Garret FitzGerald and scuttle Anglo-Irish talks. The Taoiseach had to resist pressure from within his own administration to attack Thatcher. He did reportedly describe her reaction as "gratuitously offensive." Constitutional nationalists were greatly concerned that the confusion in Anglo-Irish relations would destroy the prospects for a new political move in Ulster. The SDLP was particularly alarmed at this development, because they would have no political breakthrough with which to counteract Sinn Fein. Faced with this situation, John Hume and Irish government officials began to enlist the services of their Irish-American supporters. They contacted the Friends of Ireland and urged them to get Ronald Reagan's assistance. Constitutional nationalists hoped they could persuade the president to use his influence with Thatcher and register his concern for Anglo-Irish dialogue.[36] Among the key figures in this attempt to get Reagan's support was William Clark, former national security advisor. Clark was a long-time friend and confidant of the president. He also had a close relationship with the Irish diplomatic corps in Washington, especially Sean Donlon. Clark became very supportive of the constitutional nationalist position. While he was deputy secretary of state in 1981, Clark conducted a tour of Ireland. He greatly angered unionists when he admitted his membership of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and told a reporter, "It is the hope and prayer of all Americans that Ireland will be united."[37] Sean Donlon contacted Clark following Thatcher's "Out, Out, Out" remarks. He agreed to use his influence with Reagan to assist the constitutional nationalist cause. The president was scheduled to meet the British prime minister at Camp David on December 22, 1984. Before the meeting, Clark asked Reagan to discuss Anglo-Irish relations with the Prime Minister and to express his desire for political progress. The Friends of Ireland backed Clark in a telegram to the president on December 21. They also told Reagan of their "disappointment at Mrs. Thatcher's public peremptory dismissal of the reasonable alternatives put forward in the Forum Report."[38] American press reports that appeared after the Camp David meeting said the two leaders discussed only Western European reaction to the "Star Wars" defense initiative. Not until January 17, 1985, did the Reagan administration officially acknowledge that Anglo-Irish affairs had been on the agenda. In a letter to Mario Biaggi, the White House stated the president and Mrs. Thatcher "exchanged views on Northern Ireland" and that the president "stressed the need for progress and the need for all parties concerned to take steps which will contribute to a peaceful resolution."[39] Garret FitzGerald believes William Clark's intervention was the crucial factor in persuading Reagan to discuss Irish affairs. Against specific advice from the State Department, the president raised the issue. During the meeting, it seems that Reagan expressed a desire to see progress in the Anglo-Irish talks. He also said he would like to discuss the issue further with Thatcher when she returned to the US in February 1985. Reagan's concern with Anglo-Irish relations, and his desire for further discussions, put Thatcher under a certain amount of pressure. She was encouraged to make some new proposals to the Irish government before her return to Washington in February. Garret FitzGerald and Sean Donlon believe that American pressure played a, "decisive role in persuading Thatcher to modify her position."[40] The British thus offered a new Anglo-Irish package on January 21, 1985. This new deal was a significant advance on what had been discussed at Chequers. It offered an institutionalized role for the Irish government in the administration of Northern Ireland.[41] Although American pressure was a factor in Thatcher's more positive proposal of January 21, she was also influenced by her political colleagues in Britain. Members of her cabinet and staff emphasized that her "Out, Out, Out" remarks had damaged Garret FitzGerald's political position in Ireland and would give encouragement to Sinn Fein. They advised Thatcher to compromise and offer more significant concessions to the Irish. Despite Thatcher's new proposal, the FitzGerald administration continued to "play the American card." Sean Donlon and John Hume contacted Tip O'Neill before the British prime minister was due to address a joint session of Congress on February 20, 1985. They asked the house speaker to ensure that Thatcher discuss the Northern Ireland problem in her speech. O'Neill conveyed this request to Sir Oliver Wright, the British ambassador. To emphasize his concern, O'Neill met Thatcher on her arrival in Washington he again asked her to include the Ulster conflict in her address. O'Neill's pressure produced results. When Thatcher addressed Congress, she not only discussed Northern Ireland but was also extremely conciliatory toward the Irish government. She said that relations between her and Garret FitzGerald were "excellent" and that she would cooperate with his administration to find a political solution in Ulster. She also expressed hope that joint efforts to launch new political dialogue would receive full support from America.[42] As a complement to using its influence with Tip O'Neill, the Irish government also tried to get support from the State Department. On February 15, 1985, Peter Barry and Sean Donlon met with Rick Burt, assistant secretary of state for European affairs. They asked the State Department to include the Ulster problem in talks with Thatcher following her congressional address. Burt, because of Reagan's interest in the issue, agreed to the Irish request and succeeded in reversing the State Department's traditional avoidance of the Northern Ireland conflict. He convinced Secretary of State George Shultz to raise the question with Thatcher. At a meeting in California, Shultz and Reagan told the prime minister of their desire to see progress in Anglo-Irish discussions and offered American financial support in the event of an agreed political initiative.[43] There was considerable speculation over the nature of American governmental involvement in the Anglo-Irish process. Some unionists alleged it was all part of a sinister conspiracy under which the British would withdraw from Northern Ireland. Enoch Powell, MP, believed the US was encouraging an Anglo-Irish agreement in order to establish a united Ireland. This new state would end its neutrality, enter the NATO alliance, and permit the establishment of American military bases. Powell claimed this would greatly enhance the strategic defense of Western Europe." Perhaps a more plausible explanation of US involvement was Ronald Reagan's personal interest in Irish affairs. The president was proud of his Irish roots and was informed of the latest political developments by William Clark and other Irish Americans in his administration. These included Robert McFarlane in the National Security Council, Secretary of the Treasury Donald Regan, Secretary of Labor Donovan, and CIA Director William Casey. Irish government ministers took every opportunity to convince the Reagan administration of the threat posed by the rise of Sinn Fein. When Vice-President George Bush stopped in Dublin for talks with Garret FitzGerald in July 1983, the Taoiseach warned him that Sinn Fein political success could destroy democracy in Ireland. Irish officials reinforced this point when Reagan himself visited Ireland in June 1984. They tried to convince the president that the only way to stop Sinn Fein was through a new political agreement achieved through Anglo-Irish discussions. Reagan, as a self-proclaimed champion against world terrorism, sympathized with the Irish government and strongly opposed the IRA. Each St. Patrick's Day he issued vehement attacks against the organization and urged Irish Americans not to fund violence in Ulster. He therefore had a concrete reason for supporting an agreement that offered the prospect of stifling the republican movement. From these various influences, Reagan encouraged Anglo-Irish talks. Following the February 20 meeting with Thatcher, the British government intensified negotiations with the FitzGerald administration. Chris Ogden implies that Reagan offered to increase activities against the Irish-American republican network if the British were more conciliatory toward the Irish. He says that Thatcher partly accepted the Anglo-Irish Agreement because "If she did not, she knew she would get precious little help stopping the flow of guns and money from America to the IRA or in getting IRA suspects extradited from the US."[45] Throughout the final stages of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, the Irish continued to enlist the assistance of their American supporters. In early March 1985, Tip O'Neill led a delegation of the Friends to Dublin. They held discussions with Garret FitzGerald and Peter Barry on the progress of Anglo-Irish talks. O'Neill also went to London and assured British officials he would use all his influence to secure American financial support for a political agreement. He convinced them that, as speaker of the house, he was in a unique position to guide a financial assistance bill through Congress. In early May 1985, Garret FitzGerald traveled to Washington for further talks about the United States aid to Ireland. With Tip O'Neill and Edward Kennedy he discussed the practicalities of getting the bill through Congress. FitzGerald also went to Ottawa for a meeting with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. The Taoiseach told him the Anglo-Irish Agreement was near completion. Muironey was so delighted he promised Canadian financial assistance.[46] The final hurdle to the Agreement came in late October 1985. Charles Haughey, then leader of the Fianna Fail opposition, was dissatisfied with the Anglo-Irish discussions, believing that they were a "sell-out" to British interests. He dispatched Brian Lenihan to Washington in an attempt to convince the Friends to oppose the accord. Tip O'Neill and Edward Kennedy rejected Haughey's contentions, muted Haughey's opposition, and thereby saved the Agreement from a potentially serious challenge.[47] The months of prolonged negotiations ended on November 15, 1985, when Margaret Thatcher and Garret FitzGerald met in Hillsborough Castle and signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement. The key element of the new accord was the establishment of an Intergovernmental Conference, at which British and Irish officials would meet regularly to discuss matters relating to the government of Northern Ireland. An Anglo-Irish secretariat was also established in Belfast, to support the work of the Intergovernmental Conference. These provisions meant that the Republic of Ireland was given a formal role in Ulster for the first time since the formation of the state in 1921. Under the Agreement, Dublin formally acknowledged the right of the unionist community to remain within the United Kingdom. This was affirmed under Article One, which stated that any change in the status of Northern Ireland would come about only with the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland. Other provisions expressed a desire "to protect human rights and to prevent discrimination." The accord also promised much greater levels of cross-border security cooperation, to be coordinated by the chief constable of the RUC and the commissioner of the Garda Siochana. The unionist reaction to the Anglo-Irish Agreement was immediate and hostile. None of their political representatives had been consulted during the negotiations and they saw it as a sell out by the British. Leaders of the Ulster Unionist Party and Democratic Unionist Party embarked on a series of mass rallies and days of protest. All Unionist MPs withdrew from their seats at Westminster and eventually forced an election over the Hillsborough accord. The American reaction, in contrast, was extremely positive. The Agreement received enormous political and editorial support. All the major newspapers characterized it as a major step toward reconciliation in Ulster and praised Thatcher and FitzGerald for their political courage. The New York Times described the accord as "creative and ingenious" and warned unionists that the only group that would benefit from their opposition was the IRA.[48] The Washington Post suggested that the strong American backing for the Agreement would lead to a significant erosion of Irish-American support for the Provisionals.[49] The major Irish-American newspapers were more reserved in their reaction. All welcomed the fact that Dublin was given a formal role in Northern Ireland but questioned the unionist right to remain in the United Kingdom.[50] Mario Biaggi and the Ad Hoc Committee were also ambivalent. Though their statements seemed to support the Agreement, their phrasing left open the possibility of an attack in the future.[51] There was no such indecision in Noraid's reaction. The group followed Sinn Fein's lead in describing the Agreement as a sham and a betrayal of Irish national sovereignty. Martin Galvin reasserted that the only way peace would be achieved was through British withdrawal.[52] On the day the Anglo-Irish Agreement was signed, Ronald Reagan and Tip O'Neill held a press reception in the Oval Office. They praised the new initiative and gave concrete assurance that the United States would provide financial aid to the embryonic International Fund for Ireland. Reagan also condemned IRA supporters in America.[53]On December 9, the House of Representatives passed a resolution supporting the Agreement by a vote of 380 to 1. The resolution received a similar endorsement in the Senate one day later. The signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement brought great hope to constitutional nationalists. The political benefits promised by Dublin's role in Ulster affairs seemed to suggest a new era, in which Sinn Fein's influence would be minimized. The Agreement could be used by the SDLP to win support and reestablish its leadership of the nationalist community. Furthermore, the provisions for extensive cross-border security cooperation seemed to imply a new commitment that would severely hamper IRA operations. In America, the Friends of Ireland considered the Agreement as one of their most significant interventions in Irish politics. Tip O'Neill and Edward Kennedy firmly believed their efforts played a very important role in securing the accord. Without their sustained pressure and influence the British government would have been much less inclined to engage in serious discussions. Most significantly, the Friends and the Irish government persuaded Ronald Reagan to add his support to the Agreement. The president used his "special relationship" with Margaret Thatcher to further the process of Anglo-Irish discussions. The US contribution to the International Fund marked the first time the American government became officially involved in the Ulster conflict. Journalist Alex Brummer correctly observed: Without the encouragement and prodding of the Reagan administration and the sustained pressure for political reform from the United States Congress, Mrs. Thatcher and Garret FitzGerald may never have made it to Hillsborough.[54] The Friends of Ireland stressed that all the breakthroughs of the Agreement were achieved through political discussion. They hoped that this example would persuade Irish Americans of the futility of supporting violence and that constitutional action was the only way to bring about change in Ireland. The Friends were filled with optimism that, as the benefits of the Anglo-Irish Agreement became increasingly apparent, the republican network in America would decline to insignificance.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||