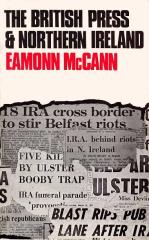

'The British Press and Northern Ireland' by Eamonn McCann[Key_Events] [Key_Issues] [CONFLICT_BACKGROUND] MEDIA: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main_Pages] [Resources] [Sources] The following pamphlet has been contributed by the author Eamonn McCann with the permission of the publishers. The views expressed in this pamphlet do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.

Published by Northern Ireland Socialist Research Centre, (1972?)

This material is copyright Eamonn McCann and is included on the CAIN site by permission of the author. You may not edit, adapt, or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use without the express written permission of the publishers. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

by Eamonn McCann

by Eamonn McCann British newspapers are wont to congratulate themselves on their high journalistic standards. The British people are encouraged to believe that their press is the best in the world. Phrases such as 'guardians of liberty' have been known not to stick in the throats of leader-writers. During the past three years, while editors and higher executives have whiled away the time in contemplation of their own ethical purity, the job went on of managing and mangling the news from Northern Ireland. Most British people have a distorted view of what is happening in Northern Ireland. This is because they believe what they read. There have been honorable exceptions. But examination of reports reveals a clear pattern of distortion. The news has systematically been presented, consciously or not, so as to justify the assumptions and prejudices of British establishment and to serve the immediate political needs of British Governments. Immediately after October 5th 1968 dozens of journalists descended on Northern Ireland. At one point the Mirror had twelve people in Derry. Few of these had any detailed knowledge of the situation. Some, mindful of the May days in France that year, spent much of their time trying to identify a local Danny the Red. Others would wander into the Bogside and ask if they could be introduced to someone who had been discriminated against. Most people prominent in the events preceding the October march had experiences such as Miss Rhoda Churchill of the Daily Mail coming to their front door seeking the address of an articulate, Catholic, unemployed, slum-dweller she could talk to. During this period the press was generally favorable to the Civil Rights Movement. Reporters and photographers were well received in Catholic areas; harassed and on a number of occasions physically attacked in Paisleyite demonstrations. Editorially, every paper backed O'Neill; who was projected as a 'cautious crusader'. There was little or none of the cruder distortion which was to come later. The coverage of Bernadette Devlin's election and entry into Parliament reflected fairly accurately the attitude of the press around this time, She was depicted as 'the voice of the student generation'. (The Sun, April 19th 1969). The Daily Mirror (April 19th 1969) said 'Swinging-that's petite Bernadette Devlin'. 'She's Bernadette, she's 21, she's an MP she's swinging . . . the girl whose honesty, vision and courage has made her the most talked of person in Irish politics for a long time'. (Express, April 19th 1969). 'Miss Devlin enthralls packed house' (The Times April 23rd 1969). There was much more along similar lines. Obviously the press at the time saw no harm in her. Despite the generally benevolent coverage of the Civil Rights campaign at this stage one could discern already the tendency to blame 'The IRA' for any violence which occurred. It was assumed for example that the IRA was responsible for the explosions preceding O'Neill's resignation. But this was mild and tentative stuff compared to what came later. The real, sustained and systematic distortion began when British soldiers came onto the streets, and by the middle of 1970 when the troops were in almost constant conflict with Catholic working-class neighbourhoods most papers had in effect stopped carrying the news. They were vehicles for propaganda. Some incidents were ignored. Others were invented. Half-truths were presented as hard fact. As far as the British press was concerned the soldiers could do no wrong. Residents of Catholic working-class areas in Belfast and Derry could see rubber bullets being fried at point-blank range, the indiscriminate batoning of bystanders and rioters alike, men being seized and kicked unconscious and then let go. As time went on and weaponry escalated some witnessed the reckless use of firearms, the casual killing of unarmed people, sometimes at a range of a few yards. They experienced the offensive arrogance of soldiers on patrol, the constant barrage of insult and obscenity, and in the British press they read of Tommy's endless patience under intense provocation, of his restraint in the face of ferocious attack, his gentlemanly demeanour in most difficult circumstances.

The other side, 'the rioters', got different treatment. They were

represented as vicious and cowardly, almost depraved in their

bloodlust To say that the press distorted the situation beyond

all recognition is not to say that those who came onto the streets

to fight British soldiers behaved in a manner which liberal opinion

would find admirable. Of course not. Riots are not like that.

In the average Northern Ireland riot neither side gives much quarter.

Verbal and physical abuse is fairly unrestrained. There are teenagers

in the Bogside who, obscenity for obscenity, could match the best,

or the worst the British Army could put up. A soldier seized by

a rioting crowd would receive much the same treatment as arrested

rioters experience at the hands of the army, But the great majority

of the British people, dependent on the press to tell them what

is happening in the North of Ireland, are by now incapable

of forming a judgement about it, so one-sided has the reporting

been. The most abiding myth fostered by the press has been the recurrent story that all riots and troubles are organised. Usually the IRA is credited with this subversive activity, but there have been other candidates, some fanciful, some farcical. On September 11th 1969, the Daily Mail splashed a story under the headline: 'Bernadette's Sinister Army'. It explained that:

'Revolutionary extremists are now in complete control of the Civil Rights movement in Ulster. Their declared aim is to turn the whole of Ireland, North and South, into a Cuba-style republic. People's Democracy, the organisation that directed the wave of protest demonstrations which brought Ulster to the brink of civil war, is riddled with Trotskyists and their sympathisers who believe in world-wide revolution . . . The present turmoil in Ulster has been conceived on Maoist-Castroist- Trotskyist lines, planned the same way and carried out with the traditional weapons of street fighters the world over . . . Posters, leaflets and revolutionary news sheets are also being printed in London for the Ulster militants, often by the International Socialists' own printing company . . . Money is also being collected for the revolutionaries. Ford shop stewards are being asked to hold a whip-round this week' As Mike Farrell commented gloomily at the time, 'I wish to Christ it was true'- A good example of the farcical approach came from Mr George Gordon who, under the headline, "Troops Fear The Croak of the Frog' reported in the Daily Sketch (June 29th 1970).

'Behind the swirling haze of CS gas, the croak of the frog summons Londonderry to riot. It blares above the crash of the gas canisters and rises over the screams of terror. It is a voice the troops in Bogside would dearly love to identify. Colourful stuff. Many a piece along similar lines has been sucked from the thumb of a reporter desperate for a new angle. Northern Ireland has been the subject of almost continuous blanket coverage for nearly three years. One would need to write a book (someone should) to deal adequately with every aspect and example of distortion. It is proposed here to direct most attention towards reports in the British national daily papers since mid 1970, and to examine some reports in detail.

One is not concerned with the tendencious editorial comment or

with run-of-the-mill journalistic, chicanery. Cynics expect such.

Nor is it proposed to deal further with reports which, while questionable,

have been relatively harmless. For example the Mail's piece

on Miss Devlin's Sinister Army and the 'Sketch 's' discovery

of the Bogside Frog indicate a certain journalistic standard,

but such stuff is not uncommon on a slow news day and in the long

term probably has small effect. On Sunday, August 16th last year, 24 year old Barry Burnett picked up a holdall which had been left by someone in Row 'O' of the stalls in the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square. He had the bag with him when he and his girl friend, Anna Korhonen, drove away in a mini. In the Charing Cross Road a time bomb in the bag exploded. Mr Burnett was seriously hurt. Miss Korhonen sustained multiple injuries and burns for which she was later awarded ten thousand pounds. Within two days the press had managed to suggest that the IRA was almost certainly responsible. It was an enormous story. On August 18th the Daily Mirror, The Sun and the Daily Sketch each gave it the whole front page. Tom Tullet and Edward Vale reported in the Mirror 'Last night Scotland Yard believed that they were the victims of an Irish Republican Army terror bomb attack.' Other papers not only indicated that the IRA was responsible but quoted anonymous police spokesmen on the possible motive. The Daily Mail said on the front page 'Police investigating the bomb that blew up a car in the West End on London on Sunday night believe the couple in the car were the innocent victims of IRA terrorists. Detectives suspect the bomb was left in the Empire Cinema, Leicester Square, as a reprisal against the arrest of Irish sympathisers.' The Daily Telegraph offered a slight variation. Describing the theory that the IRA was responsible as 'too strong to ignore', it continued: 'the activities of the Yard's Special Branch during the past few months has caused considerable concern to IRA leaders in Britain. It is thought they may have 'lost face' and want to hit back.' The other newspapers followed suit.

'One police theory is that some of the phone calls are part of a move by the IRA to reassert its importance among members discouraged by police action .'-Daily Express. Thus, millions of people were led to the belief that the IRA had planted the bomb. Since that time speakers at Irish Republican meetings in Britain have constantly been asked 'what you hoped to gain by planting bombs in cinemas?'. Yet at no time was there a shred of evidence to link any Irish group to the incident. The police have discovered no useful leads. No arrest has been made. What happened was that the image of the IRA as bloodthirsty gangsters was emphasised and reinforced. There are those who would object that, whatever the truth of the Empire Theatre incident, some more recent activities of at least one wing of the IRA are not defensible. This is not the issue. The point is that over a period of many months the British Press depicted the IRA in a way which was not based on any available facts. No subsequent events can provide retrospective justification for this pattern of reporting. The coverage of five days of fierce rioting in the Ardoyne area at the end of October and the beginning of November last year was fairly typical of such stories. The riots started after three men were shot on October 29th. These were some of the bitterest clashes Belfast had known up to that time. Stones, petrol bombs and nail bombs were used against the troops. One soldier, Marine Michael Wainwright, had his leg shattered by a nail bomb. At least fourteen other soldiers were injured. On Saturday, October 31st, the third day of the rioting, the trouble spread to Divis Street, where CS gas was used to disperse crowds, and to the Springfield Road where twenty-nine windows in the local police station were broken by stones. The Sunday Times was quite explicit about what caused the trouble. The front-page headline read 'Eighteen IRA cross border to stir Belfast riots.' The text below by 'Sunday Times Reporters' told that the eighteen infiltrators 'had orders to create. a crisis in the North likely to embarass Mr Jack Lynch . . . who faces a vote of confidence in the Dail On Wednesday. . . . Twelve of the infiltrators were born or had lived in the North for a long time . . . They travelled unarmed by car to Belfast where they picked up arms and gelignite bombs, They had an immediate impact on the streets of Belfast.' Colin Brady in the Sunday Telegraph had simultaneously discovered that 'The sudden assault on British troops and the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Belfast last Thursday, which started three days of shooting and bombing, was a calculated plan by militant Irish Republicans to dis-rupt several weeks of comparative peace in Northern Ireland's capital.' However, Mr Brady did not agree with the 'Sunday Times Reporters' contention that the motive was to embarrass Mr Lynch. His information was that 'their (the IRA's) aim is to keep the province boiling and continually focus world attention on Ulster, to the embarrassment of the Stormont and Westminster governments. Men are moving about traditionally anti-British parts of Belfast, stoking up feeling and preparing assault groups which choose their own time and place to strike.'

On Monday, November 2nd, the rest of the press followed suit.

The Sketch reported that 'IRA guerrillas have organised children

into stone-throwing gangs.' Eddie McIlwaine reported in the Mirror that 'men in black berets were seen giving orders.' The Express, too, reported that 'The Special Branch of the RUC and Army Intelligence are investigating reports that a 'provocation squad' from an illegal organisation wearing black berets were organizing the latest rioting among Catholics in the Crumlin Road and at Divis Street.' Other newspapers on November 2nd reported in similar vein. On the 3rd a report by John Chartres in The Times summed up and extended the press explanation of the causes of the riots. Having pinned responsibility for the previous days trouble on Provisional IRA agitation, he wrote: 'This is the only interpretation that can be put on any of the Catholic attacks on troops since the beginning of this year.' The Guardian editorial went further: 'When an Irishman throws a bomb at a Royal Marine he is not simply trying to kill. He wants, through murder, to provoke reprisals. His aim is a Northern Irish Sharpeville.' There are a number of unanswered - unasked even - questions raised by the reporting of this particular spate of rioting. They are questions which could be asked about the press treatment of many other incidents in Northern Ireland. For example: when the Sketch reporter wrote on November 2nd, 'IRA guerrillas have organised children into stone-throwing gangs' what exactly did he intend to convey? That he had been on the spot and seen and heard this happen? Presumably not, since there is no dramatic eye-witness account of orders being given and children deployed. Did someone tell him that this had happened? Who? If a local person, a fortuitous witness, why no quote, even an anonymous quote? Or did the information come via an army or police briefing? On the face of it this last is a not unlikely possibility. But if that was the basis of the story why was it not made clear, so that readers could understand that they were dealing with an relegation, albeit an 'official' allegation, rather than a definite fact? This question is posed even more sharply by the Sunday Times report of November 1st, quoted above. 'Sunday Times Reporters' not only mentioned the exact number of 'IRA infiltrators'-eighteen-but filled in some fairly detailed background. Twelve were either natives of Northern Ireland or had lived for some considerable time there; they were not armed on the journey to Belfast; one of their first acts on arriving in Belfast was to organise the throwing of seven gelignite bombs -again the exact number is given-at Royal Marines in the Hooker Street area. There were no ifs, buts or attributions in the story. It was set down as a straightforward and detailed account of something that had just happened. Doubtless it was accepted in this spirit by hundreds of thousands of Sunday Times readers. One can imagine that most of them found it rivetting stuff. Once again: from where did the 'Sunday Times Reporters' obtain all this information? From the army or the police? Then why not say so? And how did it happen that the representatives of no other British or Irish newspaper became aware that the authorities had discovered such dramatically newsworthy facts? If the security forces were in possession of this wealth of detail it is not easy to understand why they have never made public mention of it. To put no finer point upon it, the arrival in Ardoyne in the midst of bloody rioting of an eighteen strong squad of IRA organisers from the South is not the type of fact Army and Police spokesmen in Northern Ireland have ever been anxious to conceal. Could the information have come from an IRA source, perhaps even from one of the eighteen agitators themselves? Hardly. 'Sunday Times Reporters' have never been noticeably reluctant to evidence their 'inside' contacts. Had they got the story 'straight from the horse's mouth' we would most certainly have been told. On what then was the report based? Take the sentence: 'The 18 infiltrators from the South are said to have had orders to create a crisis in the North likely to embarrass Mr Jack Lynch, the Dublin Premier, who faces a vote of confidence in the Dail on Wednesday.' Are said by whom to have had such orders? By 'Sunday Times Reporters' certainly. Further than that we may never know. Similar questions could be raised about almost every other report of these particular riots in British newspapers. About Eddie McIlwaine's report in the Mirror of November 2nd, for example, that 'men in black berets were seen giving orders.' Seen by whom? Himself? Then why not the more convincing and dramatic 'I saw'? About Geoffrey Cooper's report in the Sketch of November 3rd which referred to a 'highly 'trained squad of thirty IRA infiltrators' who had 'unlimited supplies of gelignite'. Unlimited? How did he know?-Who told him?-Did he see it? If so, what does an 'unlimited' supply of gelignite look like? Curiously no-one managed to obtain a photograph of any of these eighteen or thirty black-bereted guerrillas despite the fact that reporters apparently could see them. It cannot have been impossible or too dangerous to take such photographs since Mr McIlwaine assured Mirror readers that 'photographs of the troublemakers were taken'. Mr McIlwaine did not say in whose possession these dramatic pictures were. No news-paper ever printed one. Perhaps one clue to the source of many of the reports is contained in the sentence quoted above from John Chartres of The Times. The riots must have been caused by IRA agitation, he says, because there is no other interpretation that can be put on them, And, indeed, if one is operating on the premise that the soldiers' behaviour is at all times Impeccable and that the people of the area involved have no genuine grievance against me army and what it represents, then it would not be illogical to conclude that they would only pitch themselves against the troops if urged, or ordered, or fooled into doing so by some outside agency. It would be the 'only interpretation' which could be put on it. And perhaps rumours, or stories leaked from 'unattributable' semi-official sources, which seemed clearly to confirm this interpretation. would seem so plausible and so reasonable as to be almost certainly true. This is a possibility. For all that none of the reporters in Belfast could have been unaware that there was a much simpler explanation for the riots starting. Late on Thursday evening, October 29th, a crowd of youths threw stones at a police car in the upper Crumlin Road. It was a minor incident. Troops were called up. Some stones were thrown at them. A relatively small crowd was involved. Up to that point the situation would not have qualified for the description 'riot'. Then Norbert Jan Bek, 27, of No 41 Marine Commando, shot and wounded Kevin McGarry, Samuel Dodds and Sean Meehan. It was not alleged by the police, the troops or anyone else that any of these three was involved in stoning or had been part of the crowd from which stones had come. Shortly afterwards the army announced that the discharge of shots had been accidental and apologised for the injuries inflicted. This incident sparked off the weekend's rioting. By the time the army apology was made-by an officer through a loud-hailer - crowds had poured out from Ardoyne and the battle, which lasted over the week-end, was joined. No-one who was in the Ardoyne area in the next few days could have doubted that the shooting of McCarry, Dodds and Meehan was uppermost in the minds of the rioters. Rioters and by-standers, in the course of the invective they directed at the troops, referred continually to it. Any reporter who, on the Friday or Saturday, asked a local resident what the trouble was about, would certainly have been referred to the incident on Thursday night. On Sunday, Mr Colin Brady's report in the Sunday Telegraph included: 'There was no specific reason why trouble should break out in Ardoyne on Thursday . . .' Marine Bek was arrested and charged with maliciously wounding three men. He was tried at Belfast City Commission on March 30th this year and found not guilty. He returned to England on March 31st, saying that he intended now to join the Australian army. The tendency immediately and without evidence to blame 'the IRA' for any atrocity which could plausibly be represented as their work, was illustrated again by the reporting of the deaths of Arthur McKenna and Alex McVicker in November last year. Mr McKenna and Mr McVicker were shot dead in Ballymurphy on November 10th. Both wings of the IRA denied responsibility. There was no record of either man being involved in politics.

No-one has ever been charged with the murders. No evidence linking

the deaths to the IRA or to any other organisation has ever been

made public. Irish journalists have since suggested that the men

may have been killed in a gangland vendetta over a gambling ring.

Whatever the facts of the matter it is demonstrable that there was never a basis for any journalist to write or any paper to print that a particular organisation was guilty. This did not prevent Colin Brady writing in the Daily Telegraph of November 17th: 'It is thought '-by whom?-'that the killers may have been members of the fanatical provisional army council which broke away from the IRA last year.' The Financial Times, likewise, reported that it was 'thought to have been an internal IRA assassination' (November 17th). The Guardian at least told us who it was had formed this suspicion of IRA responsibility: 'a gangland killing which police believe to be an IRA internal assassination' (November 17th). The Express was in no doubt: 'a boy, aged 10, saw an IRA "executioner" shoot down two men in a Belfast street yesterday.' The Sun headline was 'Boy sees IRA vendetta killing.' And so on. A precisely similar pattern emerged in the coverage of the deaths of five men in Co Fermanagh on February 9th this year. The five men, two BBC engineers and three building workers, were in a landrover on their way to a BBC transmitter along a mountain track at Brougher Mountain, near Enniskillen, when an explosion wrecked the vehicle. All five died instantly.

A few hours later the Evening News led with: 'BBC MEN DIE

IN IRA TERROR'. The rest of the press took the same line. Both

the Telegraph and the Guardian devoted their main

leaders to the incident. According to the Telegraph of

February 10th this incident and others 'bear clearly the signature

of the Irish Republican Army.' The Guardian of the same

date described it as 'the worst single incident of the new campaign

of IRA violence.' By this time the image of the IRA as ruthless cut-throats was firmly implanted in the consciousness of the British public. It was an image shortly to be given dramatic reinforcement by the coverage of the triple killing of Scottish soldiers in March, and which was constantly elaborated and strengthened by reports, articles and editorials. On March 6th, for example, under the headline '29 DIE IN GUN-LAW EXECUTIONS' the Mirror carried a story by Edward Vale telling that a 'series of twenty-nine horrifying murders have been uncovered in Ulster by Scotland Yard detectives. All the victims had been shot through the head-apparently on orders by the Irish Republican Army . . . The Yard team are hunting three IRA extremists thought to be leading the gang of executioners . . . Within forty-eight hours they had started to link up a series of mysterious deaths-first sixteen, then twenty. Since then nine more murders have been uncovered. All the victims appear to have been shot at close range, most in the back of the head. Some are thought to have been tortured before they died . . . One detective said last night 'the pattern of the killings is too similar to be a series of coincidences . . . They were shot, dragged into cars and dumped on the outskirts of Belfast".' The story obviously had some basis in a briefing given by an anonymous detective or detectives. It is not clear how many of the gruesome details came from this source and how many were the results of Mr Vale's independent fact-finding. Either way the report has some perplexing implications.

One of the deaths referred to is that of John Kavanagh, found

shot dead in Belfast in January: which leaves twenty-eight. If we assume that all the killings took place after August 1969, when the IRA re-emerged as a real force, we must understand from the report that between then and February 1971 the bodies of twenty-eight murdered men were discovered in or around Belfast. That is, on average, one every three weeks. The most perplexing thing about this is that no-one apparently noticed. Until March 6th no newsman in Northern Ireland had any idea that this wholesale slaughter was in progress. The people who stumbled on the bodies-'in ditches, hedgerows, derelict houses and on lonely roads' according to Mr Vale - kept quiet about it. More confusing" still, the relatives of the twenty-eight victims, their wives, mothers, brothers, sisters, children-maintained an equally tight-lipped silence. One wonders what they told the neighbors. The funerals, obviously, were in secret. The behaviour of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, raises even more questions. It is not clear from Mr Vale's text how many of the murders they had been aware of prior to the arrival of the assiduous team from the Yard. Manifestly, they had carried out their investigations with breathless stealth. No pictures of the various ditches, hedgerows, derelict houses and lonely roads were published. No appeals for anyone who had seen any suspicious activity in a particular vicinity around the times of the respective murders to come forward, No pictures of any of the deceased with requests for anyone who may have seen him immediately prior to the crime to contact the murder-hunt HQ. No house to house questioning. Nothing. None of the murderers was ever found. The Scotland Yard detectives have returned to London. As they left, inscrutable to the end, they made no mention of the twenty-eight dead men. Presumably the RUC continue their quiet investigations, unannounced and unnoticed, while twenty-eight Belfast families nurse their private grief and tell the neighbors that 'he's working in England'. Indeed the number may now be more than twenty-eight. It probably is. There is no reason to suppose that the IRA Execution Squad ceased operations on March 6th. If they have maintained their previous average they will have killed and dumped in ditches/hedgerows/derelict houses/lonely roads another dozen by now. One has no way of knowing. Mr Vale has never returned to the subject. Just a few days after Mr Vale's piece appeared, three Scottish soldiers were killed at Ligoniel, outside Belfast. They were killed in a reamer uncannily foreshadowed by his descriptions-shot in the head at close range. The general press coverage too echoed Mr Vale's previous story. The entire British press was seized with anti-IRA fury. The headlines and intros told their own story.

March 12th Still, on March - 13th and 14th the howl of outrage continued. Pressure mounted on both Westminster and Stormont to adopt tougher security measures. On March 16th Chichester-Clark was called to London to confer with British ministers. The result of the talks, given the press coverage, was inevitable. The public anger made it politically acceptable, indeed expedient to send more troops to Northern Ireland and to declare an intention further to repress Republican dissidence, March 17th:The advocates of 'law and order' were well satisfied. In the atmosphere of emotional recrimination they gathered strength for the final push, a few weeks later, to topple Chichester-Clark. One wonders as they contemplated the new respectability of their attitudes whether they understood how much they owed to obscure men "at desks in Fleet Street and the Grays Inn Road. Despite the fact that the Scotland Yard team investigating the death of John Kavanagh took over the case, the killers have never been found. No evidence was unearthed to link either wing of the IRA to the incident. The only persons held for questioning, and then released, were extreme 'loyalists.' A few weeks before the killing of the Scots soldiers some journalists had given a new gloss to one of the standard IRA stories - the one about the IRA organizing riots. This was in its own way as grisly an affair as any other. Some rioters in Northern Ireland are very young indeed. One sees eight or nine year old children throwing stones at soldiers. A sociologist could suggest reasons for this. The children are less conscious than adults of the dangers involved and, to some extent at least, regard rioting as play. Northern Ireland in this sense is the biggest adventure playground in the world. Whatever the explanation, anyone who has observed such children in action will know that it is difficult, well nigh impossible to dissuade them. Almost as common as child rioters are parents seeking desperately to find and to take their children out of the 'firing line'.

The British Press has not always seen it like that. Last February

there appeared a spate of stories putting an entirely different

construction on the phenomenon-that IRA men were ordering the

children to riot. The three tabloids in particular gave the story

splash treatment, with a wealth of cloak-and-dagger detail. The Mirror of February 8th led on the front page with 'Horror of the Child Terrorists.' Howard Johnson reported 'Schoolchildren are now being pushed into the front line of the terrorists' battle against British troops in Belfast . . . there have been reports of an eight year old boy hurling petrol bombs at troops . . . The tiny terrorists are used as messenger boys for IRA officers. They are also employed to spark off full-scale street battles by baiting and attacking troops.' Under the headline 'FRONT LINE KIDS' Roger Scott reported in The Sun the same day that 'IRA terror leaders here are now sending shock troops to war - their own children. Bomb-throwing eight year olds are in the front line. They steal out at dusk to play games with death, trained to hate and kill. And the children at war chant obscenities to nursery rhyme tunes as the bullets fly. The sinister parents stay in the shadows firing from behind the ranks of the young in street battles.' The Sketch headline on February 8th was 'KIDS' ARMY GOES TO WAR.' George Gordon and James Nicholson wrote that 'Rioters again ordered their children into the front line battle for Belfast yesterday.' The general picture is one from which the British public must have recoiled in horror and distaste. Millions would have accepted it as an accurate description of the situation-that parents in the New Lodge Road and Ballymurphy were indeed lurking in doorways at night having dispatched their eight and nine year old offspring, petrol bombs in hand and matches at the ready, to do battle with the British army. No-one who knows the areas or the people who live there could accept these reports. But the overwhelming majority of the readers of the Sketch the Sun and the Mirror had no such knowledge. It might not have occurred to them to question Mr Scott's statement that small children were actually being trained to kill. Mr Scott did not indicate where he unearthed this grotesque detail. Mr Scott, Mr Johnson, Mr Gordon and Mr Nicholson saw small children rioting. What they did not see - what none of them makes any claim to have seen - was these children being ordered to riot. This part of each of the three reports was based either on mere supposition or on allegations from some unnamed source. But in each case it was written as though it were incontestable fact. As for the more colourful details: one could go through each of the reports clause by clause and question whether the reporter could possibly have known this or that to be true. How could Mr Scott tell that any of the children he saw rioting was the son or daughter of an 'IRA terror leader'? Did he know them by name and actually know whose children they were? Did he notice facial resemblances to acknowledged IRA leaders? Mr Scott's intimate knowledge of Belfast neighbourhoods must make his presence there invaluable to the Sun. It may be coincidence-or it may not-that, according to Hansard, Mr Robin Chichester Clark (Unionist) said in the Westminster House of Commons on February 7th that IRA men were hiring children as 'cover' while they, the IRA gunmen, 'shelter in doorways.' One could speculate whether news-editors in London, particularly news-editors of papers locked in a circulation war, might on hearing Mr Chichester-Clark's allegation, have contacted their representatives in Belfast and asked whether it would be possible to put some flesh on this skeleton of a story. This would be mere speculation. One is not certain it happened. One could not therefore state it as fact. Other, more minor examples of British papers without evidence linking the IRA to atrocities, imagined or real, are legion. On May 9th this year for example someone threw a petrol bomb at the home of Mr John McKeague, militant protestant leader of the Shankhill Defence Association. The premises caught fire and Mr McKeague's seventy three year old mother was burned to death. Shortly afterwards the RUC issued a statement saying that they did not believe the incident to have had 'any sectarian significance'. In the Northern Ireland context this meant clearly that they did not believe the IRA was responsible. Unimpressed, the Daily Telegraph next day carried a headline on the front page 'MOTHER DIES IN IRA BOMB FIRE.'

The Daily Telegraph really warrants a study of its own.

At one time this year there was a short period of complete peace.

Since the Telegraph concluded from almost any week's events

in Northern Ireland that the IRA ought to be put down immediately

one wondered how, exactly, it would handle this new situation:

'It has always been part of the IRA's tactics to intersperse outrages

with periods of relative inactivity, designed to encourage complacency.'

Editorial 1st April 1971. Not very long before its collapse a Daily Sketch editorial described the average British soldier as: 'a great defender of civilization against chaos, of order against the apostles of violence. He is the most patient decent, military man in the world'. (17 July 1970)

This accurately describes the archetypal British soldier as projected

in reports from Northern Ireland. Allegations of misbehavior by

troops has usually been dismissed as at best mischievous, more

probably subversive. When the behaviour of soldiers was such that

it could not be defended outright, excuses could be found and

allowances made. One could take as an example Simon Winchester's

description of an incident in which a soldier beat a young girl

to the ground as 'regrettable and embarrassing, yet highly understandable.'

(Guardian, 3rd August 1970) The next day, Max Hastings, describing how a soldier beat a youth so viciously so as to break his baton on his head could make it sound like a jolly adventure, more Biggies than Belfast: 'As the riot squad moved up they banged their shields with their batons in rhythm with their marching time, then, at a yell from their officer they sprinted into the darkness among the crowd to return dragging a youthful rioter. The whole Company cheered spontaneously. 'Broke my baton, this one: said a Corporal cheerfully holding up the stump.' (Evening Standard, 4th August, 1970) The most instructive instance of a story being so arranged as to present the army in the best possible light is probably the reporting of the killing of Mr Bernard Watt in Butler Street, Belfast, on February 6th this year-in particular the reporting in The Guardian. Mr Watt, aged 28, was not a member of any political organisation. He had played no prominent part in public events. Some of the phrases used to describe him in the press in the few days after his death were curiously similar: For example 'Watt was a well-known agitator' (Evening News, 6th July 1971). 'Watt was a well-known Republican agitator' (Sunday Times, 7th July 1971). 'Watt was said to be a Republican agitator' (Observer, 7th July 1971). The final London edition of the Guardian (February 6th, 1971) said that, 'an army marksman shot dead one rioter, who threw two petrol bombs at an armoured car in Butler Street, off Crumlin Road, Belfast. The dead man was Bernard Watt, aged 28, of Hooker Street'. The report was headed 'by Simon Winchester'. On April 6th Bernadette Devlin raised this report in the House of Commons and alleged that it had been 'concocted in the editorial offices of the Guardian, to condone the cold blooded murder of one, Barney Watt.' The Guardian was cut to the quick. It defended itself in an editorial two days later and then, after receiving a letter from Miss Devlin, re-stating the original charge, recalled Mr Winchester from holiday to clear the matter up. His account of the way the report was put together was published beneath Miss Devlin's letter. It is an illuminating document. Mr Winchester's account of the killing was, he said, written for the penultimate Manchester edition of his paper. It was written at a time when Mr Watt was not yet known to have died. It included the line 'the army shot and wounded a rioter who threw two petrol bombs.' In a passage which deserves quoting in full, Mr Winchester went on to explain why he had so described the dead man.

'I certainly presumed Mr Watt's guilt as a rioter and said as much in the report I wrote for the penultimate Manchester edition. However, unpalatable that may be to Miss Devlin, I think it perfectly fair and reasonable to term anyone in a group from which petrol bombs and bricks were being thrown 'a rioter'. The army has to be more circum-spect; a soldier cannot legally shoot 'a rioter' thus described. He has to wait until a man has committed one of a number of specific offences, of which throwing petrol bombs is one. I accepted at the time that this is what Mr Watt must have done, and this I duly reported.'

Mr Winchester's reasoning is instructive. The rule book says that

a soldier can only shoot some-one who has, for example, thrown

petrol bombs. A soldier had shot Mr Watt. Mr Watt must,

therefore, have thrown petrol bombs, 'and this I duly

reported'. The evidence which convicted Mr Watt Mr Winchester says that he 'sent no further copy that night on Mr Watt's death', since other events, including two further deaths, necessitated his leaving the scene of the first fatality. From where, then, did the final London edition, the subject of Miss Devlin's original charge, get its more detailed information? Mr Winchester explains that too. 'The late London edition names Mr Watt as a petrol bomber because the army press officer said he was'. The text as it appeared gave no hint of this. The allegation from the army press officer was inserted without inverted commas, or any other attribution, and headed 'by Simon Winchester'. Whether or not this transgresses the accepted ethics of news reporting is something which those who believe in such putative concepts must decide. At any rate Mr Winchester was clearly unhappy about the way the story had finally been presented. A feature article published two days after the killing (February 8th) offered a very different account of the event. 'The army', he wrote, 'shot and killed Bernie Watt as they might have shot an Arab guerrilla - not for what he had done but for what he was.' (It may have been in the interests of balanced reporting that Mr Harold Jackson was dispatched to Northern Ireland four weeks later to write [Guardian, 12th March 1971] 'In Aden they [the British Army] pursued what amounted to a counter terror campaign. The Crater area was eventually subdued by the expedient of ensuring that potential assassins were gunned down by carefully stationed snipers the moment they made themselves evident. There were a number of questionable decisions taken by the men behind the cross-wire sights in what was little more than a three second trial. There is no conceivable political situation in which any of this could be applied in Ulster'.)

It is not being alleged that Mr Winchester's standards are lower

than those of other journalists covering Northern Ireland. They

are higher if anything. After reflection he did try to repair

some of the damage done by the pieces attributed to him on February

6th. His reports are worthy of examination because Miss Devlin's

statement in Parliament forced a public examination of the way

they were compiled. Two factors operated to have Mr Watt dubbed a petrol bomber-the immediate instinct of the reporter on the spot to put the best possible construction on the army action, and the automatic and uncritical acceptance by London newspaper offices of statements made by the army press office. These facts are discernible in most British press reports of army activities. They are seen most clearly when the army kills somebody. Officially soldiers are not permitted to shoot to kill an ordinary rioter. They are allowed to shoot to kill petrol bombers, nail bombers, gunmen, etc. In order to maintain that the army is behaving correctly it is therefore necessary to show that anyone shot by a soldier was, in fact, in one such category. This has led to the application of a variation on the American army's dictum in Vietnam: 'If he's dead, he's a VC.' 'If he's dead', runs the assumption underlying many a press report 'he was carrying a petrol bomb, or a nail bomb or a gun.' Examples abound. The case of Bernard Watt was one. The killing of Danny O'Hagan in the New Lodge Road on July 31st last year was similar and notable for the fact that it drew from one reporter, John Chartres of The Times, a feat combining unusual verbal dexterity with mental agility, which it would be a pity not to unearth. The army said that O'Hagan had been throwing petrol bombs. Local people were vehemently insistent that he had not. Local belief that O'Hagan had been completely unarmed was so furiously and loudly expressed that most papers in this case hesitated to tell the army story as fact. Of the daily press only the Mail, (1st August 1970), reported bluntly that O'Hagan had been killed 'as he tried to throw a petrol bomb'. Mr Chartres wrote a piece on Northern Ireland for The Times Review of the Year (31st December, 1970). The O'Hagan case presented him with some difficulty. He could not describe him flatly as 'a petrol bomber', since an undeniable doubt had been established. Mr Chartres resolved the matter as follows:

'The 12th itself passed without incident, but there was further serious rioting in the New Lodge Road area and the army for the first time carried out its threat to shoot at assistant petrol bombers. One civilian was killed.' (What do 'assistant petrol bombers' do? Hold coats?) Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beatty were killed in Derry on July 9th. There were numerous civilian eye witnesses to each killing and these were unanimous that neither was armed. Yet a number of papers quite automatically reported an army press statement as straight news. 'Bomb man shot dead in Ulster' ran the Mirror headline (July 9th, 1971) about Beatty. Cusack 'had been seen carrying a rifle' (Sun), 'was carrying a rifle after he had been warned' (Times). Linking the two deaths together the Express reported 'Bomb Man No. 2 shot dead.'

William McKavanagh was one of those shot dead by the army and

posthumously co-opted into the IRA. He was killed in the market's

area of Belfast on August 11th. The posthumous recruitment of Mr McKavanagh Tom Conyers and Philip Evans reported in the Daily Telegraph (12th August, 1971): 'The first gunman killed yesterday was shot by soldiers of the Royal Green Jackets during the siege of a bakery in the Market's area . . . About 300 troops who advanced on the building under a hail of bullets after a siege lasting several hours burst in to find one gunman lying dead. Two surrendered and several others were arrested.' 'Sun reporters' wrote: 'A terrorist group occupied a bakery in the city's market area . . . Troops advanced into the building under a fierce exchange of fire. They found a man lying dead. Two more were arrested The dead man was William McKavanagh'. In the Times Tim Jones and Robert Fisk reported that 'a young man was shot as troops fought to gain control of a large bakery complex taken over by gunmen. After bloody exchanges they took the building and arrested two men, one of whom was armed.' A Daily Mail reporter wrote a dramatic blow by blow account of the engagement. 'The battle of the bakery began in Belfast at 3.50 am yesterday . . . the terrorists raked the streets with a Thompson sub-machine gun and .303 and .22 rifles. The fighting was savage . . . One gunman was killed . . . By 5.15 two of the gang, one still armed, had been captured.' The Express more cryptically said that 'The Green Howards fought for five hours for a bakery taken over by gunmen. The soldiers captured two snipers and found a third dead.' In the Evening News, Iain Macaskill wrote that 'the sniper died when troops fought their way into a bakery. The Guardian's 'own reporters' stated that 'another man was found dead by the army and two more were arrested after a siege in the city's market area. It began on Tuesday night when terrorists took over a bakery in Eliza St.' What happened was this: William McKavanagh was walking towards his home in Henrietta St. early on 11th August with his brother Patrick and his cousin Edward Rooney. He was carrying a pair of fishing waders and a pair of socks which had been looted. At the corner of Catherine Street and Cromac Square, some one hundred and fifty yards from the bakery referred to in the press reports, a soldier called on him to halt. Frightened that the stolen goods might be discovered he ignored the call. He was shot dead. Patrick McKavanagh and Edward Rooney were seized by the troops and beaten unconscious. The story as it appeared in the British papers had come from the army press office in Lisburn. Every British paper reported it as fact. None indicated that it was an army statement. The facts were gathered from eye-witnesses including Edward Rooney and Patrick McKavanagh by an Irish Times reporter, Michael Heney. He put the case to an Army Press Officer who replied: 'There was a lot of confusion about that night. In fact there was no sniper shot on Inglis's factory, that is correct .' No British newspaper printed this statement. The special relationship between the press and the army was illustrated even more recently by coverage of the deaths of two children. Seventeen month old Angela Gallagher was killed in Belfast on September 3rd. Annette McGavigan, fourteen, was killed in Derry on September 6th. Someone took a shot at a British army patrol in Belfast. The bullet missed, ricocheted off a wall and struck and killed Angela Gallagher. Both wings of the IRA denied responsibility. The incident happened in a Catholic area and it is a reasonable suspicion - to put it no higher - that the shot was fired by someone, perhaps an independent operator, of Republican sympathies.

Annette McGavigan was killed by a British Army bullet aimed, accor-ding

to the army, at a sniper. The headlines used to announce these

two deaths were significantly different in their emotional content.

There is no conscious conspiracy to distort the situation. Pressmen do not get around a table and decide to twist the truth in an agreed direction. Still there is a certain apparent co-ordination and this is not accidental. It happens because the press in general serves a certain interest, and whether individual journalists are conscious of it or not, whether they like it or not, the news as published will tend to support that interest. In the aftermath of October 5th the central thrust of British government policy was directed towards the 'democratisation' of Northern Ireland. The increasing British investment in the Republic, the growing importance of the South of Ireland as a trading partner, made dangerously obsolete the traditional attitude of previous governments - one of un-critical support for the Unionist party in the North. For the first time in the history of Anglo-Irish relations it suited the Imperial power to balance between the Orange and the Green. This was automatically reflected in British policy towards the North. It involved a resolution to force concessions to the Catholics. It was reflected too, in the press. It offers an explanation of many pro-Civil Rights editorials, of the curious treatment of Bernadette Devlin, of the fact that the Catholic case received enormously more coverage than the Protestant case. One can remember arguing with journalists that they ought at least to visit the Fountain Street area in Derry and talk to the Protestants. Few did. One of the functions of the British Army when it came onto the streets was to supervise and to enforce the reforms which had already been promised and those which were to emanate from the Hunt Report. Another of its functions was to see that things did not go beyond that. The interest of big business required the democratisation of the state -i.e. that the Specials be disbanded, the police disarmed, discrimination eliminated. It was not in its interest that, to take a random example, the state be overthrown. It was quickly clear that there were those within the Catholic community, and with some influence especially in the barricaded areas, who wanted to go much further than British policy dictated, and in the press a very clear differentiation was made between these and the more reasonable elements. The Mail story on Bernadette's Sinister Army was an early example of this but it was with the emergence of the IRA as a force to be reckoned with that press attitudes solidified into the outright hostility evidenced by consistent misreporting. Once 'the IRA' had been identified as the main enemy all concern for fact melted marvelously away. The stories of IRA mass murders, IRA extortion and intimidation, IRA men training children to kill etc. served to justify increasingly repressive measures to the British public It was on this basis that The Guardian, self-appointed keeper of the British liberal conscience, was able plausibly to support internment. It was as a result of such stories that politically the British Government could operate the policy. The British press is in a constant state of adaptation to the needs of the British ruling class. This happens because the Press is not an independent institution. There is no 'free press.' It is locked into the structure of society. Newspaper owners like to pose as fearless, independent-minded rather swashbuckling characters. Occasionally, in the boozy atmosphere of the annual get-togethers they have been even known to talk of their 'love' of newspapers. But a cursory examination of newspaper ownership shows what nonsense this is. Every British national newspaper is, either directly or through its major shareholders linked to other big businesses, inextricably enmeshed in the capitalist system. The Daily Mail and General Trust Limited, for example, owns Associated Newspapers Ltd. Through Associated Newspapers it is involved in Television (Southern Television Ltd.), docks, (Purfleet Deep Wharf and Storage Co and Taylor Bros Wharfage Ltd.), Transport (W.West Haulage Ltd.), Mining (Rio Tinto/Hamilton Group); in all, in fifty subsidiary enterprises. The News of the World Organisation (News of the World, The Sun) has interests including engineering, retail newsagents, transport, and betting shops. The International Publishing Co-the Mirror Group-merged in 1970 with the Reed Group of companies. It is involved in a bewildering multitude of activities. The group has four hundred associated and subsidiary companies. It is involved in plastics, engineering, building, transport, wallpapers, TV, films, theatres etc, etc. It has vast city and financial interests. It has overseas possessions in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Holland, South Africa, Hong Kong, Nigeria, the Republic of Ireland, France, Germany, Italy and the United States. The Thompson Organisation (The Times, Sunday Times) has one hundred and ninety two subsidiaries and associated companies. It has substantial holdings in Scottish Television, in package tour companies, and in transport. It has overseas interests in South Africa, the United States, Zambia, Rhodesia, New Zealand, Malawi, Jamaica, Gibraltar, Canada and Australia. Even those papers which are formally independent have on their boards men who are simultaneously directors of other, outside businesses, The Observer, for example, is controlled by a board of trustees and prides itself on its resultant independence. Chairman of the Board is Lord Goodman who has twenty seven directorships, at the last available count. Others involved included the Hon NCJ Rothschild (thirty-one outside directorships, including textiles, property companies and investment companies) and various Astors and associates, all of whom have other business interests. There is no such thing as an independent national newspaper. Those who have ultimate control over what is printed and what is not are drawn from a relatively tiny segment of society-the owners of big business. Generally speaking, what is printed tends to support their interests. The more paranoiac members of left-wing groups believe that this happens because press barons order editors who in turn order reporters, to tell lies. The actual process is marginally more subtle. In the first place the editorship of a national newspaper is a responsible position and 'responsibility', as understood by the owners of newspapers, would be incompatible with the belief, say, that private ownership of industry is a bad thing. One of the qualifications for editorship is, naturally, a general acceptance of the owners' attitudes. This is reflected in the editorial 'line' of every paper and it filters through to reporters, sub-editors etc. A journalist who has covered N Ireland for a British Daily paper explains 'You must remember that every journalist wants what he writes to appear, and in practice all journalists know pretty well what their paper's line is, what is expected of them. There is a fair amount of self-censorship. This happens without thinking. No journalist I have met writes what he knows will be cut. What would be the point? If he has a story which he knows will cause controversy back at the newsdesk he will water it down to make it acceptable.'

Most journalists rely heavily on 'official' sources. This explains

the sometimes striking similarity of coverage. Stories from 'official'

sources will, of course, be eminently acceptable. Moreover, as

a former Mirror employee writes, 'In a situation like Northern

Ireland our people would have to keep in close touch with the

Army Press Office. It would be more or less part of their job

to get to know the army press officer as well as possible and

that in itself would affect their judgement a bit. Then one of

their biggest preoccupations is not to be scooped by a competition.

No-one on The Mirror would be sacked because he didn't

come up with a carefully authenticated and researched piece, written

from local hard work. You do get sacked if the rival has a sensation

about the IRA.' Even if a reporter does send through copy which is critical of the establishment and its representatives (eg the army) it is at the mercy of the news editor and the sub-editors. These are likely to be the most conservative of all the journalistic staff, with years of grinding-practice in what is acceptable to the editor and the management. The average senior sub-editor will, as a reflex action, strike out any sentence which jars his sense of propriety. A reporter still working in Northern Ireland for a 'quality' daily says ' . . . However, a few lines cut here and there which can completely alter the tone of the piece is almost impossible to argue about. You get bland apologies that cuts were made for reasons of length and yes, the subs should have referred back to you but after all it was near the edition time and we're all professionals. It is never admitted that the cuts are those sentences which are critical of the army, or which make the point that Faulkner is not entirely accepted by the whole Ulster community. If you push it they tell you that you are imagining things. You can end up thinking that you are. There's nothing you can do about it.' Reporters who know what is expected of them; news editors and sub-editors trained to recognise and eliminate 'unhelpful' references; editors appointed with 'sound' attitudes; boards of management composed of substantial businessmen: the whole sprawling machinery of news gathering and publication automatically filters, refines and packages the information fed in and works to ensure that the news, as printed, is fit to print. The general picture is enlivened by occasional bursts of maverick radicalism. A 'fearless expose every now and then helps to maintain the official myth of the independent press (and can be good for circulation) but does not alter significantly the pattern which emerges.

'On dangerous issues - the behaviour of the army, a power workers'

strike-the pattern will emerge clear and stark. Newspapers tell

lies. The news from Northern Ireland has been a compound lie.

A free press would be one disentangled from the whole system of private ownership. Recently some journalists-for example many of those involved in the Free Communications Group-have become disenchanted with the manipulation of news such as is evidenced in this pamphlet. No longer content merely to feed their unused stories to Private Eye, they now seek to remedy the situation by demanding a 'democratic' press. By this they mean some form of 'journalists' control', the right of journalists to sit on company boards or to have a say in formulating editorial policy.

This is trendy nonsense. As shown above,

the newspaper industry is an integral and necessary part of the

capitalist system. It cannot be detached from it and its problems

dealt within isolation by some minor internal restructuring. The

fight to free the press to tell the truth is the fight to end

the system which needs to destroy truth.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||